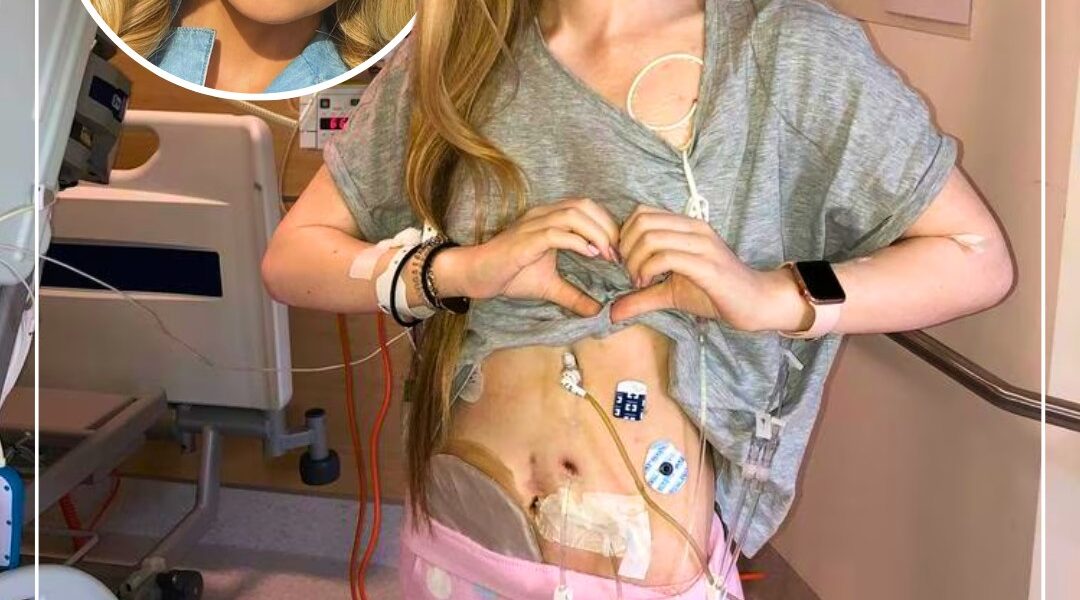

Young Woman With Rare Terminal Illness Chooses to End Her Life Through Voluntary Assisted Dying

At 25, most people are wrestling with first mortgages, career choices or wedding plans; Annaliese Holland is deciding how, and when, her life will end. After growing up in and out of hospital with a rare neurological autoimmune disease that has left her in multi-organ failure and constant pain, the young South Australian has been approved for voluntary assisted dying, a legal option where she can choose to die on her own terms. Yet alongside that decision, she has also been quietly building something for the living, shaped by the grief of losing her best friend and the stark clarity that comes with knowing time is short.

The Rare Disease Behind Annaliese’s Decision

Before she was old enough to finish high school, Annaliese Holland’s body had already turned against her. From childhood, she bounced between hospital wards with severe nausea, vomiting and pain, while her bowel behaved as if it were blocked, despite scans showing nothing there.

At 18, after years in paediatric care, she finally received a diagnosis: autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy (AAG), a rare autoimmune disease in which the body attacks the autonomic ganglia, the nerves that control involuntary functions like heart rate, blood pressure, digestion and urination. In practical terms, it means systems most of us never think about have to be constantly managed just to keep her alive.

Because her stomach stopped emptying properly, Annaliese was placed on total parenteral nutrition (TPN), fed through IV lines for the past decade. Those same lines have repeatedly exposed her to life-threatening infections; she has survived sepsis 25 times. By 22, doctors told her the illness was terminal. Now 25, she lives with multi-organ failure and the cumulative damage of years of aggressive treatment.

“Life for me now is getting up each day doing what I need to do medically, taking the painkillers, trying to get through the day, just to go to bed and do it all again,” she has said. For Annaliese, AAG is not an abstract diagnosis. It is a daily negotiation with survival, made on a body that can no longer reliably sustain her.

A Life Shrinking Around an Illness

As Annaliese’s illness progressed, it did not just weaken her organs. It steadily stripped away the future she imagined for herself. Long-term steroid use and powerful medications have left her with severe osteoporosis. She has fractured her spine in four places and cracked her sternum, at one point placing such pressure on her heart and lungs that even breathing became precarious. Necrosis in her bones has caused her teeth to blacken and fall out.

These are not isolated medical events, but layers of loss. While friends moved through milestones such as formals, graduations, 18th and 21st birthdays, engagements and babies, she spent those same years in hospital wards. “Everyone’s life is moving and I’m just stuck. I’m not living. I’m surviving every day, which is tough,” she has said.

Annaliese describes living with her condition as “walking on a field of landmines” – never knowing which day will bring another medical emergency or near-death experience. The uncertainty is not just frightening. It is exhausting, turning each day into another round of survival rather than a life she can meaningfully plan or inhabit.

Choosing Voluntary Assisted Dying

For Annaliese, the decision to pursue voluntary assisted dying did not arrive suddenly. It emerged after years of surviving close calls, resuscitations and invasive treatments that no longer offered real hope of recovery.

The turning point came after yet another collapse in hospital. Having been brought back once more, she pleaded with her father: “Dad, please let me go. I will not hate you if you let me go.” She later told him, “If this happens again, I don’t want anything… I’m happy with [you] saying no to treatment.” It was only then, she recalls, that he said he understood she had “had enough.”

Her mother still quietly hopes for a miracle, but also recognises the scale of what her daughter endures. That tension is common in families facing end-of-life decisions: the instinct to cling to any chance of more time sits alongside the knowledge that more time often means more suffering.

In Australia, medical aid in dying is now legal in every state for terminally ill, mentally competent adults who meet strict criteria. Patients must be assessed by multiple doctors and undergo a psychological evaluation. After a three-week process, Annaliese was approved.

She describes VAD as her “safety blanket” and admits she cried with relief when she heard the decision. “I think it’s so weird to be happy, but I was so happy when I found out I was approved,” she said. For her, VAD is not about giving up, but about finally having a say in how her story ends.

Creating Meaning in the Midst of Dying

While preparing for her own death, Annaliese has been quietly focused on what she can leave behind for others who grieve. After losing her best friend, Lily Thai, to a terminal illness, she found herself drawn to Lily’s grave, talking to her, writing letters and sitting in silence. Those visits became “emotionally cathartic”, a place where grief felt less suffocating.

One day at Adelaide’s Centennial Park, as she knelt to place flowers, a note blew past her. Looking around, she noticed other letters scattered on the grass. That moment sparked a question: could there be a safer, more intentional way for mourners to send messages to those they had lost?

She researched similar ideas overseas and then approached cemetery management. The result is Echoes of Love, a dedicated letterbox at Centennial Park where anyone can post a private message to a deceased loved one. Centennial Park CEO Nadia Andjelkovic has emphasised that there is no limit to how often it can be used, and all letters remain confidential.

For Annaliese, who lives with multi-organ failure and has been approved for voluntary assisted dying, the project is deeply personal. “Living with a terminal illness has helped me confront the realities of death and made me recognize the need to break the stigma, creating better avenues for young people to talk about death and grief,” she has said. She hopes the letterbox offers others the same sense of comfort and connection it brings her.

What Annaliese’s Story Asks Of Us

Annaliese’s choice sits at the fault line of some of our hardest questions. How do we measure quality of life when medicine can prolong the body but not ease relentless suffering? What does autonomy look like when a young woman, fully informed and mentally competent, says she has reached her limit?

Voluntary assisted dying is tightly regulated in Australia, reserved for people who are terminally ill and meet strict safeguards around capacity and consent. It is not the same as suicide in the context of mental illness or emotional crisis, and it exists alongside, not instead of, palliative care. Ethicists often emphasise that the challenge is not only whether such laws should exist, but how society supports patients and families who must live with these decisions, whatever they choose.

Annaliese cannot control her disease, but she has tried to reclaim meaning: in her advocacy, in creating Echoes of Love, in speaking honestly about pain, fear and love. Her story invites us to do a few simple but difficult things. Talk more openly about death and serious illness. Listen when people describe suffering we cannot see. Support better palliative care and mental health services. And if we are grieving, find our own

Featured Image Source: Annaliese Holland’s GoFundMe