I discovered a suicide note in my Harley’s saddlebag that didn’t belong to me.

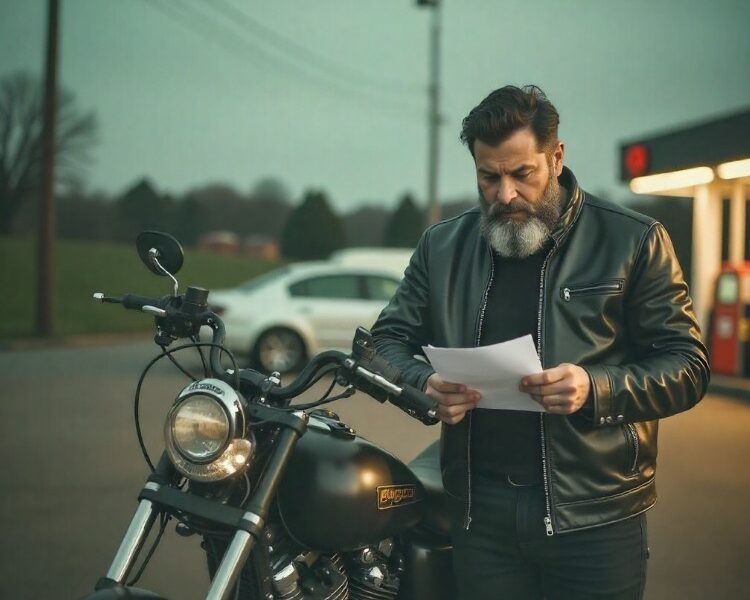

I was wiping dust from my old Harley in the parking lot behind Murphy’s Diner when the whole thing started. Murphy’s is my Wednesday habit: one black coffee, one slice of apple pie, and a nod to the cook who knows my name. I’m sixty‑eight, long gray beard, leather jacket that belonged to a friend who never came home from the war. Same diner, same seat, same comfort.

That morning I parked next to a battered Honda Civic covered in college stickers. I remember thinking the driver must be a student glued together by cheap coffee and hope. After my pie I carried two bags to the bike—my own faded saddlebag and another black one that looked almost identical. I didn’t notice I’d mixed them up until I stopped at a grocery store on the way home. Inside the extra bag was no loaf of bread or box of cereal. Instead, a folded sheet of paper fell out.

The note was shaky, written in neat but tired handwriting. “I am twenty‑three,” it began, “and I do not see a future.” The writer signed only “Emma.” She set the date for tomorrow, December 15, at three in the afternoon. She picked Riverside Bridge—the tall one west of town where the river roars loud enough to drown a scream.

I read the note twice. My hands shook like they used to when I came back from Vietnam. Emma wrote that she had left medical school, was swimming in two‑hundred‑thousand dollars of debt, and had caught her fiancé in bed with her best friend. Worst of all, she believed nobody would notice if she was gone.

I knew that kind of midnight thinking. Forty‑two winters back I parked my own bike near that same bridge at three in the morning. I had ghosts in my head, booze in my blood, and gravel in my soul. I planned to jump. An old biker named Frank saw my Harley, figured out the rest, and sat with me until daylight. He told jokes, shared silence, and refused to let me die. Because of Frank I woke up to another sunrise. Now, decades later, I held Emma’s letter and realized it was my turn to pay the debt forward.

Digging deeper in the bag, I found anatomy books full of bright highlighter marks and a hospital badge for St. Mary’s. Emma Chen, third‑year med student. Her eyes in the photo looked brave but empty. An energy‑bar wrapper and an almost‑empty pill bottle for anxiety told the rest of her story: tired, lonely, stretched thin.

I started my Harley and rode straight to St. Mary’s. The garage felt like a maze, but after twenty minutes I spotted that same little Honda. A ticket on the dash said she’d parked at five in the morning. She’d been inside ten hours already.

At the information desk I asked for Emma Chen. The clerk said, “We have several Emmas. Last name?” I showed the badge I’d found. She sighed. “Students can’t be paged. Check back at lunch, about noon.”

Noon felt too late. The note said three. I wandered every hallway, chatting up janitors and nurses. Most shrugged until a resident with red eyes and a half‑eaten muffin finally nodded. “Yeah, Emma’s on pediatrics this week. Eats lunch in the cafeteria. Looks rough lately.”

At a quarter to twelve I sat near the cafeteria doors and watched white coats drift in like weary birds. Then I saw her. Same face as the badge but smaller, like worry had shrunk her. She bought only coffee, no sandwich, and sat alone at a table.

I walked over, heart pounding. “Emma Chen?” She jumped. I set her bag on the table.

“You grabbed the wrong bag at Murphy’s,” I said. Her cheeks lost color; she knew what I’d read.

She tried to stand. I gently motioned for her to stay. “Riverside Bridge, three o’clock,” I said. “That’s in less than three hours.”

Tears filled her eyes. “Please, give me the bag. Forget everything.” Her voice was thin like cracked glass.

“I can’t,” I answered. I rolled up my sleeve and showed the faded scars on my forearm. “Different war, same bridge.

She covered her mouth. We sat in noisy silence while doctors hurried around us.

At last she asked, “What kept you alive that night?” I told her about Frank. About how he refused to leave, how sunrise felt like proof that life could go on.

“Does the pain ever stop?” she whispered.

“It changes,” I said. “Slowly.” I pulled out my phone and showed her a picture of my daughter, Rebecca, smiling in blue scrubs. I told Emma how Rebecca once failed her board exams and thought her life was over, but she tried again and now saves strangers in the ER.

Emma hugged herself. “I owe two hundred grand. I failed my boards twice. I’m all out of second chances.”

“Your parents would rather hear you broke than hear a eulogy,” I said. “Debt is money; death is forever.”

She gave a tiny laugh filled with tears. “You don’t get Asian parents.”

“I’ve seen plenty of grieving parents,” I answered. “Trust me, they’d choose a breathing daughter every time.”

She tried to stand again. “I need to finish rounds.”

“No,” I said softly. “Today you’re taking a sick day. We’re going for a ride.”

“I don’t ride motorcycles.”

“First time for everything.” I slid my spare helmet—silver with a fading peace symbol—across the table. After a long moment she reached out and took it.

Outside, she called her attending, voice trembling: “I’m not well. I have to leave.” Then she followed me to the Harley. She climbed on behind me, arms rigid. I told her to hold tight. She squeezed like life depended on it––and maybe it did.

I didn’t head for Riverside Bridge. I pointed north, toward Canyon Lake and the Veterans Motorcycle Club lodge—quiet, safe, far from temptation. The road curled under oaks and pines. As miles rolled by, her grip slowly eased. On gentle bends I felt her lean with me instead of against me.

At the lake we killed the engine. The world grew still—just water, wind, and a few ducks complaining about nothing. She removed the helmet, hair messy, eyes less empty.

“That was terrifying,” she said, “but also… freeing.”

We sat on a wooden bench. She talked. I listened. She told me about long nights of study, the pressure to be perfect, the fiancé who said her stress was “bad energy,” and the best friend who proved him right. She spoke of student debt that felt like a chain around her future. I nodded, never judging.

I told her how I dropped out of college after the war, became a grease monkey, then went back to school at forty‑five. How my parents were upset until they saw I was alive and smiling. How life rarely follows the map we draw at twenty.

She wiped her eyes. “I still feel like quitting.”

“Quitting med school isn’t the end,” I said. “Quitting breathing is.”

We needed backup. I called Rebecca. She drove out on her break, still in hospital blues. She and Emma talked doctor talk I barely followed. Rebecca admitted she’d failed boards once, too, and had spent months in therapy. She said some shifts still broke her heart, but most days felt worth the fight. Emma listened like a dry sponge soaking water.

Three o’clock came and went. No one stood on a bridge. Emma was still here.

“I should tell someone about my thoughts,” she murmured.

“You will,” I agreed. Rebecca scribbled a therapist’s name and a crisis line on a scrap of paper. Emma folded it like treasure.

As we watched the sun slide lower, Emma asked, “Why did you bother? You don’t know me.”

“Because Frank bothered,” I said. “Because one stranger’s kindness saved my life. That makes every stranger my responsibility.”

“The biker code?” she asked.

“The human code,” I said. “Bikers just wear it on our sleeves.”

We rode back to St. Mary’s. She gave back the spare helmet, eyes swollen but hopeful. “Can I call you if darkness comes back?” she asked.

“Any hour,” I promised. “And if the line is busy, leave a message. I’ll ride over.”

Six months later a picture lit my phone: Emma in fresh scrubs holding a certificate. She’d passed her boards on the third try. Her text read: “Still here. Still fighting.”

I sent the picture to Frank’s daughter. Frank died ten years back, but his kindness lives on. She replied, “Dad would smile.”

Emma stayed in medicine, moved into pediatric oncology, and found a new partner who treats her right. She still carries debt but also carries life. Every December fifteenth she mails a card. Last year’s showed her first baby, cheeks round like a peach. The note said, “Her middle name is Frances—after Frank, after you, after everyone who stops to notice.”

That card hangs in my garage above the workbench, next to an old black‑and‑white photo of Frank and me leaning on our bikes at dawn. Two stubborn men, one gone, one riding, both part of an unbroken chain.

People think motorcycling is about chrome and noise, but it’s really about eyes wide open. You notice the quiet car in a lonely lot at midnight. You notice the tired kid crying into her coffee. You notice a stranger whose life is dangling by a word, a look, a chance. When you notice, you stop. You sit with them in their shadow until sun climbs back up the sky. That’s the ride that matters.

And sometimes, if fate’s feeling playful, you pick up the wrong saddlebag at a diner and stumble into exactly the mission you were born for.

Because out on the road—or in the world in general—there’s only one rule that counts: nobody jumps alone if we can help it.