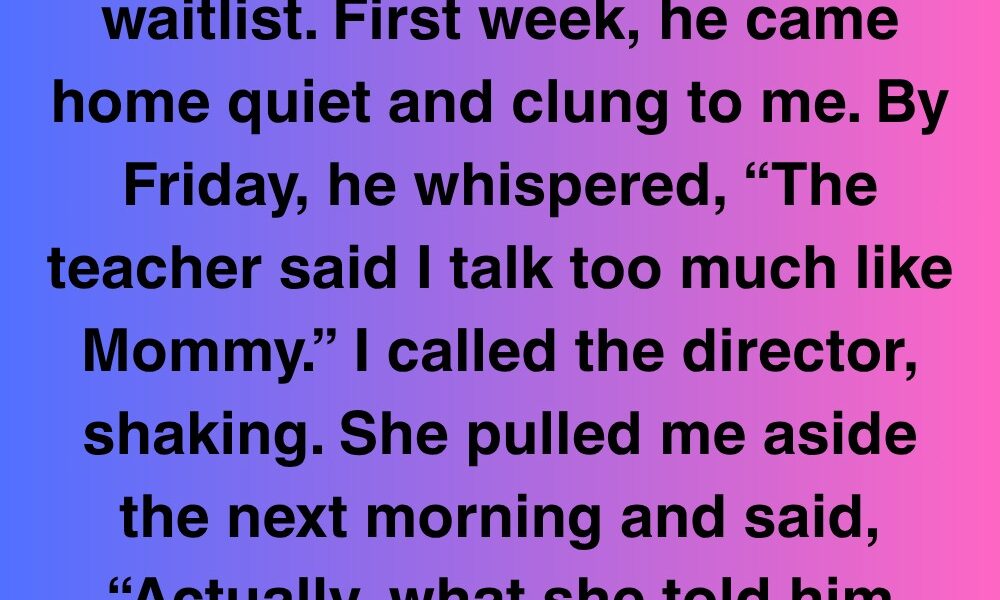

I finally got my son into a decent preschool after months on a waitlist. First week, he came home quiet and clung to me. By Friday, he whispered, “The teacher said I talk too much like Mommy.” I called the director, shaking. She pulled me aside the next morning and said, “Actually, what she told him was that sometimes when we’re too chatty, it can distract others who are trying to focus.”

Her tone was calm, almost rehearsed. I nodded, but something in me didn’t settle.

My son, Theo, had always been talkative. Not disruptive—just curious. He asked about the sky, about why toast got brown, why birds flew south. His little brain was always spinning, and I never wanted to be the parent who squashed that. So hearing he’d been told to “tone it down,” even gently, hit a nerve.

Over the weekend, I tried not to dwell on it. I reminded myself that preschool was new for him—and for me, too. But come Monday, I noticed a change. Theo hesitated before answering questions. He’d glance at me after he spoke, like he was checking if it was “too much.” It broke my heart.

That night, I asked, “Do you like your teacher?” He shrugged. “She says I talk like a grown-up,” he muttered. “She says it’s confusing for the other kids.”

I sat there in silence, holding his little socks in my hands. Something didn’t feel right.

Midweek, I volunteered for library hour at the school, hoping to observe without hovering. I brought Theo’s favorite picture books and helped a few kids pick theirs out. When Theo’s class came in, I saw his teacher, Miss Berman—a woman in her late thirties with perfectly straight hair and a tight-lipped smile—usher them in with practiced efficiency.

Theo reached for a book on the solar system, but Miss Berman put it back and handed him a book about colors instead. “Let’s try something simpler today,” she said.

He looked crushed.

After story time, I thanked her for letting me help. She nodded but didn’t ask about me, or Theo, or even thank me back. Maybe I was being sensitive, but when she spoke to the kids, her tone had an edge. Not cruel—but cold.

Later, I brought up the solar system thing with the director, Miss Harmon. She was polite but quick. “We trust our educators to make developmentally appropriate choices. Every child has different needs.”

I went home and cried.

The next day, I ran into another mom in the parking lot. Her name was Salma, and her daughter Noor was in Theo’s class. She mentioned how Noor had stopped pretending to be a “doctor” at home because “someone at school said doctors were boys.” My stomach turned.

“You think it was a kid?” I asked.

She shrugged. “Could be. But Noor said ‘a grown-up said it.’” She gave me a long look. “You’ve noticed things too, huh?”

That conversation lit something in me.

Over the next few weeks, I kept a quiet eye. I watched how Theo hesitated when we practiced letters. I overheard him telling his cousin, “I can’t ask why too much at school. It’s not allowed.” I stayed in touch with Salma, who started texting me little things Noor said after school. Another parent, Dan, joined in, saying his son was told to stop drawing “silly things” and focus on “real art” like houses and trees.

It started forming a picture.

But here’s where the twist began.

At the next parent-teacher meeting, I went in prepared. I had notes, examples, even screenshots of our parent group chat. I wasn’t there to attack—I just wanted to raise concerns. But before I could open my folder, Miss Berman spoke first.

“I know some of you have had concerns,” she said smoothly, folding her hands. “But I want to reassure you all—I follow the curriculum and uphold classroom standards. Some children may feel challenged at first, but school is about learning boundaries.”

My mouth went dry.

The director was there too, nodding in agreement. I glanced around the room. A few parents looked uncomfortable, but no one spoke. Except Salma. She raised her hand.

“Respectfully,” she began, “children shouldn’t feel smaller when they leave school than when they arrive.”

That cracked the ice.

One by one, parents began chiming in. Not everyone had the same experience, but enough shared little stories—dismissed questions, discouraged ideas, sudden shifts in personality—that a pattern emerged. By the end of the meeting, Miss Berman looked rattled. So did the director.

A week later, I got a call from the school.

They were “re-evaluating classroom dynamics” and bringing in a child development consultant. It felt like a win, but honestly, it was just the start.

I still worried. Theo still paused before speaking sometimes. We started calling it his “thinking breath,” and I gently reminded him it was okay to ask questions. “That’s how you learn,” I’d say.

But the real twist came two months later, when the consultant’s report was shared—privately, not publicly.

A friend of mine on the PTA let me peek. It said something I didn’t expect: “Classroom environment leans toward rigid structure; teacher shows signs of burnout; unintentionally discouraging critical thinking among advanced verbal students.”

Unintentionally. That word stuck.

I sat with it for a while. Maybe Miss Berman wasn’t mean, just… worn out. Maybe she wasn’t trying to dim Theo’s light. Maybe she just didn’t know how to handle kids who colored outside the lines.

And I thought about all the teachers out there—underpaid, overstretched, expected to be saints and therapists and babysitters all in one. It didn’t excuse everything, but it helped me understand.

Miss Berman quietly took a leave in spring. The new substitute, Mr. Niles, greeted each kid at the door with a high-five. When I picked up Theo on his first day with him, he ran to me, grinning. “Mr. Niles says I’m like a little professor!”

We laughed the whole way home.

But here’s where it really came full circle.

At the end-of-year talent show, Theo insisted on doing a presentation about volcanoes. He wore a little suit jacket and held up his hand-drawn diagrams with shaking fingers. When he started explaining lava tubes, I could see the nerves in his eyes. Then something beautiful happened.

Halfway through, he said, “I used to be afraid of talking too much. But I’m not anymore, because people need to know cool things!”

The room clapped. I wiped tears off my cheek.

Afterward, Miss Harmon came over. “He’s come a long way,” she said. I just smiled and replied, “He was always that way. You just needed to see it.”

A few parents came up to me that day—some who’d stayed quiet earlier. One dad said his son had started drawing superheroes again. Another mom thanked me for “speaking up when the rest of us were still unsure.”

It wasn’t just about Theo. It never was.

This whole experience taught me that advocacy starts small. It’s asking one question. It’s trusting your gut when something feels off. It’s not about fighting teachers—it’s about fighting for kids to feel safe, curious, and seen.

And sometimes, the very thing you’re worried is “too much”—your child’s voice, your own questions, your instinct to speak—is exactly what’s needed to make something better.

So speak up.

Ask.

Don’t let anyone make your child—or you—feel like they’re too much.

If this story made you think about your own experiences with school or parenting, give it a like or share it with someone who needs a reminder that little voices matter.