The Veterinarian Said the Dog Would Never Feel Joy Again, but the Morning He Forced Himself Upright and Tried to Wag, an Entire Police Station Forgot How to Breathe

The Veterinarian Said the Dog Would Never Feel Joy Again, but the Morning He Forced Himself Upright and Tried to Wag, an Entire Police Station Forgot How to Breathe

The Veterinarian Said the Dog Would Never Feel Joy Again, but the Morning He Forced Himself Upright and Tried to Wag, an Entire Police Station Forgot How to Breathe

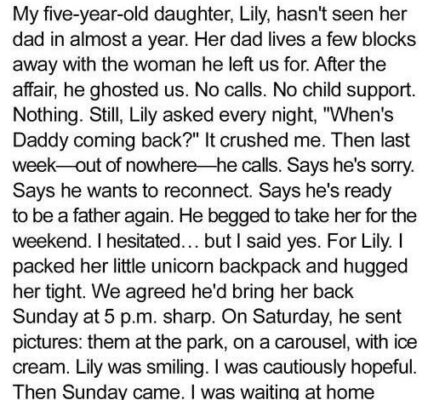

I had worn a uniform in this city long enough to understand that grief does not announce itself loudly most of the time, that it prefers to move quietly through people’s lives, settling into their posture, their tone of voice, the way they stop making plans for the future and start measuring everything by how much energy it will cost, and by the time this story truly began I had already spent thirty-two years learning how to stand in the middle of other people’s worst days without letting my own hands shake.

My name is Thomas Hale, and for most of my adult life I was known not as a man but as a rank, a badge number, a voice on the radio that stayed calm when others were losing control, and I had come dangerously close to believing that this was all I was ever meant to be, a function rather than a person, a witness rather than a participant, which made it easier to believe I was ready for retirement, ready for the quiet, ready to put distance between myself and the kind of suffering that had become routine enough to feel almost dull.

That illusion lasted until a morning when the rain fell so relentlessly it felt punitive, as if the sky itself had decided the city deserved to be scrubbed raw, and dispatch sent me to a stretch of road no one ever claimed as part of their neighborhood, a forgotten industrial artery called Blackstone Way where rusted fencing leaned like exhausted men and the air always smelled faintly of oil and old water.

The call came through with the kind of casual phrasing that only exists when the person saying the words does not yet understand their weight, a trucker reporting “road debris,” something dark on the shoulder near the drainage culvert that might cause an accident, and I acknowledged it without urgency because experience had taught me that ninety percent of the time this meant a blown tire, a pile of scrap, or the remains of an animal already beyond help.

The wipers on my cruiser worked furiously but still failed to keep the windshield clear, smearing streetlights into pale halos and turning the road into a slick black mirror that reflected everything except clarity, and as I drove I felt that familiar fatigue settle into my bones, the kind that does not come from lack of sleep but from knowing you have been carrying the accumulated weight of other people’s losses for decades without ever setting it down.

When my headlights finally caught the shape on the shoulder, I slowed instinctively, my foot easing off the gas before my brain fully registered what my eyes were seeing, because something about the way the shape lay felt wrong, not limp enough, not abandoned in the careless way death usually leaves things behind.

I parked, stepped out into rain that soaked my uniform within seconds, and walked toward the ditch with my flashlight cutting a narrow tunnel through the downpour, already rehearsing the motions in my head, the quick check, the report, the push back from the roadway, the mental distance I would create to get through the rest of the shift.

Then the shape moved.

Not a twitch caused by water or wind, but a deliberate, trembling shift, and when the beam of my flashlight caught an eye, wide and amber and alive with a terror so pure it felt almost accusatory, my body reacted before my mind did, my hand freezing mid-reach as every internal alarm I had honed over thirty years went off at once.

The dog did not growl, did not bare teeth, did not even attempt to move away, as if whatever instinct normally told an injured animal to defend itself had been replaced by something else entirely, something closer to resignation, and when he exhaled the sound was long and broken, a sound that carried exhaustion rather than aggression, and in that breath I heard a history of pain that did not belong to an accident.

I crouched slowly, speaking without thinking, my voice dropping into the tone I used for victims pulled from wreckage or children found hiding after a domestic call, soft and steady and stripped of authority, because authority meant nothing to a creature who had clearly learned that power only led to hurt.

“It’s okay,” I said, though I had no idea if that was true, and when my fingers brushed his side his entire body convulsed in a violent flinch that made my stomach tighten, a reflex born not of the moment but of memory, and the sound he made then, a high, raw scream that cut through the rain like a blade, forced me to pull my hand back as if I had touched something burning.

I angled the light downward, and the sight stole what little breath I had left.

His front legs were not simply broken, not twisted in the chaotic way impact usually leaves behind, but bent backward at angles that suggested intention rather than chance, swollen grotesquely, skin split and inflamed, infection visible even to an untrained eye, the smell rising from the wounds confirming what logic already knew, that this damage was old, days old at least, inflicted and then left to fester.

I had seen what cars did to animals. This was not that.

For a long moment I simply sat back on my heels in the rain, my knees soaking through, my flashlight trembling slightly despite my efforts to steady it, and felt something inside me harden into a shape I did not recognize as professional detachment, something closer to anger, sharp and focused and deeply personal.

I thought about all the reports I had written that ended with no suspects, all the cases that went cold because cruelty does not always leave fingerprints, all the times I had been forced to accept that some harm would never be answered for, and I looked at this dog, still alive despite everything, and felt that acceptance fracture.

I called dispatch and told them to cancel the hazard report, my voice clipped and controlled, then said I was taking an animal to emergency care and would be unavailable, and I did not wait for permission because something about the situation felt too urgent for protocol.

I took off my patrol jacket, heavy and waterproof, and wrapped it carefully around the dog’s torso, shielding the ruined limbs from movement, and when I lifted him he weighed far less than he should have, all bone and fear and stubborn survival, and I warned him quietly that this would hurt because lying felt disrespectful.

He did not scream again. He went slack in my arms, whether from pain or shock or the simple relief of being held by someone who was not going to finish what others had started, and I placed him gently on the passenger seat, turned the heat up until the vents blasted warm air, and drove like a man trying to outrun something he could not see.

The emergency clinic was bright and unforgiving, all white walls and harsh lights, and when I burst through the doors carrying a mud-soaked jacket wrapped around a broken dog, the staff reacted instantly, the receptionist already calling for a vet before I could speak, because some situations announce themselves without explanation.

The veterinarian on duty was a man named Dr. Elias Monroe, older than most, his hair gone almost completely gray, his movements efficient but unhurried in the way of someone who has learned that panic helps nothing, and when he peeled back the jacket and saw the damage he went still for half a second, that brief human pause before professionalism reasserts itself.

They moved fast, pain medication, IVs, warm fluids, hands working with practiced coordination, and I stood uselessly against the wall, rainwater pooling at my feet, watching a stranger fight for the life of a dog I had known for less than an hour and already felt unaccountably responsible for.

After what felt like both minutes and years, Dr. Monroe turned to me, his expression grave but not unkind, and explained with careful clarity what my gut already knew, that the damage to the front legs was catastrophic, that nerves were destroyed, that infection had spread, and that without immediate amputation the dog would not survive the week.

Both front legs, at the shoulder.

The words landed heavily, reshaping the room around them, and when he added that most people in this situation chose euthanasia, citing quality of life, cost, and practicality, I surprised myself by answering without hesitation, telling him to do whatever it took to save the dog’s life, because something deep inside me rejected the idea that survival should be conditional on convenience.

Dr. Monroe studied my face for a long moment, as if assessing whether this resolve was real or simply the adrenaline of the moment, then nodded and said they would do their best, but I needed to understand that the road ahead would be long, painful, and uncertain, and that there were no guarantees of happiness waiting at the end.

“I’m not asking for happy,” I said, though I did not fully understand why that distinction mattered so much to me. “I’m asking for alive.”

The surgery took hours, and I spent them sitting in a plastic chair, staring at a wall clock whose ticking seemed indecently loud, thinking about how easily my life had been diverted by a call labeled “debris,” and how little control any of us actually had over the moments that defined us.

When Dr. Monroe finally emerged, his scrubs marked, his posture heavy with exhaustion, he told me the dog had survived the operation, that the infection had been worse than expected, but that his heart had held, and I felt my knees threaten to give way in a way they never had after shootings or fatalities or any of the other things I told myself were worse.

I saw the dog in recovery, wrapped in bandages, his chest narrow and altered, his eyes half-open and unfocused from medication, but when he saw me he lifted his head a fraction, just enough to acknowledge my presence, and something about that small effort broke through a wall I did not know I had built.

I named him Calder, because the word meant strength carried through fire, and because he had already endured more than most living things ever should.

Taking Calder home changed the shape of my days immediately and completely, turning routine into ritual and silence into something fragile rather than peaceful, because he panicked whenever I left the room, cried when he could not see me, and slept only if my hand rested on his side, as if my continued existence needed constant confirmation.

I carried him everywhere, fed him by hand, learned to support his weight with towels and slings, and there were nights when exhaustion pressed so heavily on my chest I wondered if love alone was enough to sustain either of us, yet slowly, almost imperceptibly, his eyes began to change, the vacant stare giving way to curiosity, then to something like intent.

I had no one to leave him with when my leave ended, so I did the only thing that made sense to me and brought him to the precinct, setting up a nest of blankets in a quiet corner of the break room, half-expecting resistance and instead finding something closer to reverence, as hardened officers encountered the reality of a creature who had lost almost everything and refused to disappear.

Calder dragged himself at first, then pushed, then experimented, his back legs growing stronger, his movements more deliberate, and over weeks of effort and countless falls, he began to lift his chest, to balance, to stand in brief, trembling moments that drew an audience every time.

The night he finally managed to stay upright long enough to look around, tail twitching uncertainly as if remembering something it had almost forgotten, the room went silent, and men who had faced down armed suspects without flinching felt tears gather without shame.

The true twist came months later, when a child brought into the station after a violent incident froze at the sight of uniforms and radios and noise, until Calder approached on his hind legs, strange and scarred and undeniably alive, and in that moment of shared brokenness something shifted, fear loosening its grip enough for words to return.

From then on, Calder became a presence in places where words failed, a bridge between pain and expression, until one final act of instinct led him to save a missing boy in freezing conditions, pushing his already failing body beyond its limits and paying the price with his mobility entirely.

When the veterinarian told me Calder would never walk again, that his spine had suffered irreversible damage, I did not feel despair, only a quiet certainty, because the dog who had taught himself to stand had already shown me that movement was not the same as purpose, and that dignity did not depend on the shape of a body.

I retired early, moved to a place where the ground was flat and the days were slower, and learned a new way of living centered around wheels instead of legs, sunsets instead of sirens, and a dog who rolled beside me with an expression that suggested he knew exactly how much he had changed my life.

Life Lesson

Not every soul that survives will return to the shape it once had, but survival itself is not a compromise, and when we stop measuring worth by wholeness and start recognizing courage in persistence, we discover that even the most damaged bodies can carry unbroken purpose, and that sometimes healing does not mean going back, but learning how to move forward in an entirely new way.