- Homepage

- Interesting

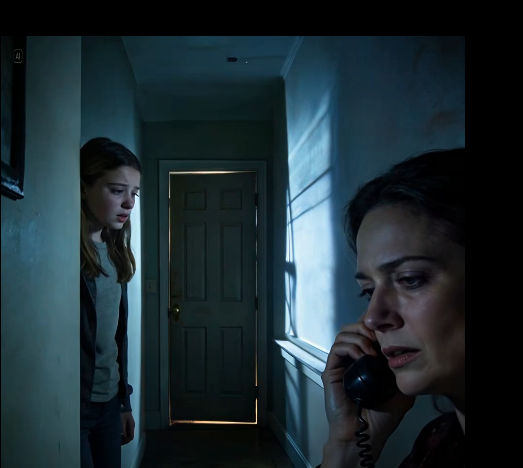

- My stepmother was always kind, gentle, and treated me like her own child. Until that night, when I heard her speaking on the phone: “As long as the girl dies… all the inheritance will be ours.” And at that exact moment… my bedroom door slowly opened

My stepmother was always kind, gentle, and treated me like her own child. Until that night, when I heard her speaking on the phone: “As long as the girl dies… all the inheritance will be ours.” And at that exact moment… my bedroom door slowly opened

My stepmother was always kind, gentle, and treated me like her own child. Until that night, when I heard her speaking on the phone: “As long as the girl dies… all the inheritance will be ours.” And at that exact moment… my bedroom door slowly opened.

My stepmother was always kind, gentle, and treated me like her own child. Until that night, when I heard her speaking on the phone: “As long as the girl dies… all the inheritance will be ours.” And at that exact moment… my bedroom door slowly opened.

For most of my life, I thought I’d gotten lucky.

My stepmother, Marianne Hart, didn’t arrive in our home like the villain people warn you about. She arrived like relief. She learned my favorite cereal without asking. She showed up to my school concerts with flowers. She brushed my hair on mornings my dad had early meetings and told me, softly, that it was okay to miss my mom—because love didn’t compete, it expanded.

When my father married her, everyone said the same thing: “You’re blessed.” And I believed it, because Marianne’s kindness wasn’t flashy. It was consistent. The kind that makes you stop waiting for the other shoe to drop.

Then my father died.

A sudden heart attack on a Tuesday morning. One second he was reminding me to bring a jacket, the next he was gone. The house turned quiet in a way that didn’t feel peaceful—more like the world had swallowed its own sound. Marianne held me through the funeral, her cheek pressed to my hair, and when people came up to tell her she was “so strong,” she nodded with a trembling smile.

Afterward, she kept being kind. Too kind. She served soup I didn’t ask for. She insisted I rest. She offered to handle “all the complicated paperwork” because I was “still a child.” I was sixteen, but grief can make you smaller. So I let her.

That night, the house felt too large. I lay awake listening to the radiator click and the wind scrape the branches against my window. I was halfway into sleep when I heard Marianne’s voice—muffled, careful—coming from downstairs.

I didn’t mean to eavesdrop. I only sat up because something in her tone wasn’t the tone she used with me. It was tighter. Sharper. Like she was holding a smile in place with her teeth.

I crept to the top of the stairs and listened.

“As long as the girl dies…” Marianne said, low and steady, “…all the inheritance will be ours.”

My blood turned to ice so fast I nearly lost my balance.

There was a pause, as if someone on the other end asked a question. Marianne exhaled, impatient. “Not ‘if.’ When. The trust is written that way. I checked. She’s the obstacle.”

My lungs forgot how to work. I backed away from the stairs silently, every nerve screaming at my legs to move faster. I reached my bedroom door, slipped inside, and eased it shut.

I leaned against it, shaking, trying to convince myself I’d misunderstood. Maybe she meant something else—some legal phrase, some metaphor. But there’s no harmless way to say as long as the girl dies.

And then I heard it.

Footsteps in the hallway. Slow. Approaching.

My bedroom door handle turned. The door creaked inward as if the house itself had decided to betray me.

I barely had time to dive under my blankets. I turned my face into the pillow, forced my breathing to slow, forced my body to soften as if sleep had already claimed me. My heart hammered so violently I was sure she could hear it.

The door opened wider. The hallway light spilled across my carpet. I felt her presence before I heard her—like the air thickened with perfume and purpose.

Marianne didn’t speak. She stood there for a long moment, and in that silence I understood something with a clarity that terrified me: if she believed I’d heard her, kindness would no longer be necessary.

I kept my eyes shut. Kept my mouth slack. Kept pretending.

A soft sound—fabric rustling—moved closer to the bed. Then her shadow crossed my blanket.

She leaned down, close enough that I could smell peppermint on her breath. Her voice came out gentle, almost loving. “Sweetheart?” she whispered.

I didn’t answer.

Her fingers brushed my hair—slow, careful, like a mother checking on a child. Then she straightened, and I heard the smallest sigh, as if she’d confirmed something.

The door clicked shut.

Only when her footsteps faded did I let my eyes open. I stared at the ceiling, shaking so hard my teeth hurt, and realized the truth that destroyed every safe memory I had of her: Marianne wasn’t kind. Marianne was patient.

And now she had a reason to stop being patient.

I didn’t sleep after that. I lay there until dawn, replaying the sentence again and again like my brain could grind it into something less real. When morning finally arrived, Marianne moved through the kitchen as if nothing had happened. She hummed softly, poured me orange juice, asked if I wanted pancakes.

Her gentleness was so perfect it felt like mockery.

“Big day,” she said lightly. “We’ll meet Mr. Kline this afternoon. The lawyer. Just to go over your father’s estate.”

My fingers tightened around my mug. “Okay,” I managed.

She smiled. “Good girl.”

The words landed wrong. Not affectionate—possessive. Like I belonged to a plan.

I needed three things, and I needed them fast: proof, safety, and someone who wasn’t charmed by Marianne Hart.

So I did what I’d never done before. I stopped acting like a grieving child and started acting like someone who wanted to stay alive.

While Marianne went upstairs to “take a call,” I used my phone to record the sound of my own voice, shaking but clear, describing what I’d heard. I didn’t want it to live only in my head where fear could rewrite it. Then I texted my best friend, Tessa: Can you stay on call with me all day? Don’t ask why. Just please. Tessa responded immediately: Yes. Always.

Before the lawyer appointment, I went to school early and told the guidance counselor, Mrs. Owens, that I didn’t feel safe at home. I didn’t say “my stepmother is planning to kill me,” because even speaking that felt like stepping off a cliff. But I said enough: I heard something, I’m scared, my father’s estate is involved, I need help. Mrs. Owens didn’t try to comfort it away. She asked practical questions. She documented. She made me promise to come back to her office after the meeting.

At 2 p.m., Marianne and I sat in Mr. Kline’s conference room. Framed degrees. Soft carpet. A box of tissues placed like decoration. Mr. Kline spoke warmly about my father, about “his wishes,” about “stability for you, Eliza.”

Then he opened the folder and read the part Marianne wanted me to hear.

“The Hawthorne property and remaining liquid assets are placed into a trust for Eliza Hart,” he said. “Principal to be distributed at age twenty-five. Education and medical disbursements permitted before then.”

Marianne nodded solemnly, like she was proud of my father’s responsibility.

Then Mr. Kline continued, and the room shifted.

“In the event of Eliza’s death prior to age twenty-five,” he read, “the trust shall transfer to the surviving spouse, Marianne Hart, or any issue of the marriage thereafter.”

I felt my skin go cold again. So that was the sentence Marianne had meant. As long as the girl dies…

Marianne’s hand found my knee under the table, squeezing gently as if we were a team. I wanted to vomit.

I forced a small smile and said the only thing that kept me from shaking apart in front of them. “Thank you for explaining. It’s a lot.”

Mr. Kline nodded sympathetically. Marianne smiled like an angel.

On the drive home, Marianne talked about “fresh starts” and “new routines” and how we would “honor your father by living well.” She even suggested I take a sleep aid that night because I looked “so tired.”

I watched her hands on the steering wheel and understood a new layer of danger: she didn’t just want the money. She wanted it to look inevitable. Natural. A tragedy. The kind of tragedy people would pity her for.

At home, I didn’t lock myself in my room. I didn’t accuse her. I did something safer: I played along long enough to set my own trap.

When Marianne offered me tea that evening, I took it, carried it to the kitchen, and poured it into the sink when she wasn’t looking. Then I washed the cup, drank water from a sealed bottle, and made sure she saw me brushing my teeth as if everything was normal.

At 9 p.m., I told her I had a headache and wanted to sleep early. She kissed my forehead and said, “Of course, sweetheart.” Her voice was perfect.

In my room, I didn’t sleep. I packed a small backpack—passport, charger, a change of clothes, the death certificate copy I’d found in Dad’s file, and the name and number Mrs. Owens had given me for a family services advocate. I left my window slightly unlatched—not to climb out, but so it would be obvious if someone tried to stage a “break-in.”

Then I did the hardest thing: I called my father’s sister, Aunt Naomi, the one Marianne always described as “dramatic” and “jealous.” Naomi answered on the second ring.

“Eliza?” she said, startled. “Honey, what’s wrong?”

I swallowed. “I need you to listen,” I said, voice shaking. “And I need you to believe me.”

Naomi didn’t interrupt. When I finished, she went quiet for a moment—then her voice changed into something hard and protective. “You are not staying there tonight,” she said. “Do you hear me?”

“I can’t just—” I started.

“Yes, you can,” Naomi cut in. “You’re coming to my house. I’m calling an attorney. And I’m calling the police non-emergency line to make a report. Tonight. Before anything happens.”

Tears burned my eyes, but not the helpless kind. The relieved kind. Because someone had finally stepped into the room with me.

Ten minutes later, Marianne knocked on my bedroom door. “Eliza?” she called softly. “Are you asleep?”

I didn’t answer.

The handle turned slowly.

This time, I wasn’t pretending.

I was already on the line with Aunt Naomi, and my phone camera was recording, face-down on my nightstand. I heard the faint click of the door opening, the whisper of Marianne’s footsteps, the pause by my bed.

Then her voice, so gentle it could’ve fooled anyone. “Poor girl,” she murmured. “So fragile.”

Fragile. That was how she saw me: not a person, a problem to be removed.

I didn’t move. I waited until I heard her step away again, and only then did I exhale.

In the morning, I left for school as usual—backpack on, hair brushed, good girl mask on. Marianne waved from the porch like a loving guardian.

By lunchtime, I wasn’t at school anymore.

I was with Aunt Naomi and a lawyer who spoke in the calm, sharp language of protection.

And the day Marianne believed she controlled began slipping out of her hands.

The first thing Naomi’s attorney did wasn’t dramatic. It was decisive. She filed an emergency petition for temporary guardianship and requested an immediate hearing, citing credible fear, documented statements, and the new financial motive established by the trust language. She also advised Naomi to request a welfare check at my home—not to “catch” Marianne, but to create an official record that I had left due to fear and that adults were now aware.

“People like Marianne rely on disbelief,” the attorney said. “They rely on everyone thinking, ‘She’s so kind, she would never.’ We are going to take that advantage away.”

When the police came to Naomi’s house to take my statement, I told them what I’d heard. I told them about the trust clause. I gave them the timestamped voice note I’d recorded that morning. I gave them the name of my school counselor who could confirm I’d reported fear before leaving. I didn’t embellish. I didn’t guess about methods. I stuck to facts, because facts don’t crack under pressure.

That afternoon, Marianne called me forty-seven times.

Her first voicemail was sweet. “Eliza, honey, where are you? You’re scaring me.”

The second was sharper. “This is unacceptable. Come home.”

By the fifth, the mask slipped. “If you’re with Naomi, she’s poisoning you. Your father warned me about her.”

By the tenth, her voice became something I had never heard from her before—cold and furious. “You have no idea what you’ve done.”

The hearing was scheduled for the next morning.

Marianne showed up in a pale cardigan and a careful expression that screamed “concerned stepmother.” She brought tissues. She brought a friend from church. She brought Mr. Kline’s assistant as a character witness. She sat with her hands folded like a saint waiting to be wronged.

Then the judge asked a simple question: “Why is the child afraid to return home?”

My attorney played a short portion of the recorded audio from my room—Marianne’s voice, near my bed, calling me “fragile,” and the earlier voice note I’d made immediately after overhearing her. Not a cinematic confession. Not a smoking gun. Something better: a pattern of intent, motive, and proximity that could not be waved away as teenage drama.

Marianne’s face didn’t crumble. Not yet.

But it tightened—like a person realizing she’s no longer performing for an audience that wants to be charmed.

The judge granted temporary guardianship to Naomi pending investigation and issued an order limiting Marianne’s contact with me. Supervised only. No private calls. No home visits. No “accidental” encounters.

Marianne left the courtroom with her jaw clenched, eyes bright with a rage she couldn’t display without breaking her image.

Two days later, I learned the part that made her truly panic: the trust.

My father had included a second clause—one Marianne either didn’t know about or didn’t understand until now. If Marianne was found to have acted to harm me, threaten me, or manipulate guardianship proceedings for financial gain, she would be disqualified as a beneficiary. The trust would transfer instead to a charity my father supported, and Naomi would become trustee until I turned twenty-five.

In other words: the moment Marianne tried to turn me into a casualty, she turned the money into smoke.

And that was when their lawyer called.

Not my lawyer. Hers.

He didn’t call to threaten. He called to control damage.

I was sitting at Naomi’s kitchen table when Naomi put the call on speaker. Marianne was in the background on her end, breathing too loudly, like she was standing just off-frame.

“Mrs. Hart,” the lawyer said, voice tight, “you need to understand the seriousness here. Your position in the trust is now at risk. If the investigation finds any evidence of coercion, intimidation, or harm, you will lose everything under the disqualification clause.”

Silence. Then Marianne’s voice, strained: “That clause wasn’t supposed to—”

“It is in the document,” he cut in. “And it’s enforceable. You need to stop contacting the minor immediately, comply fully with supervision, and do not—do not—attempt any private access.”

Naomi watched my face carefully. My hands were steady now, but my stomach still felt like it was learning gravity from scratch.

Marianne’s face went pale not because she was caught being cruel.

She went pale because she was caught being greedy.

The investigation didn’t resolve overnight, but my life had already changed. I stopped measuring safety by how kindly someone smiled. I started measuring it by what they did when no one was watching. I started therapy. I stopped apologizing for needing protection. And I began to re-read my father, not as a distant man, but as someone who had tried—too quietly, too late—to build safeguards I never knew I’d need.

The last time I saw Marianne in person was during a supervised exchange of my belongings. She stood in the doorway of the house that used to feel like home, eyes glossy, voice soft with rehearsed sorrow.

“I loved you,” she said.

I looked at her and felt something settle into place—painful, clear. “You loved what I stood between you and,” I replied.

Then I walked away without running.

And for the first time since my father died, I felt the smallest hint of something I hadn’t expected to feel again: control.

If you were in my place, would you confront Marianne the moment you heard that call—or would you do what I did and build a case quietly first? And do you think the scariest betrayals are the loud ones… or the ones wrapped in kindness?