Mother Arrested After Courtroom Incident During Child’s Murder Trial

Marianne Bachmeier was born in 1950 in Germany. Her early life was marked by instability and trauma. She later spoke publicly about experiences of abuse and hardship during her youth.

As a teenager, she became pregnant and gave her first child up for adoption. A second child followed under similar circumstances.

In 1973, she gave birth to a daughter, Anna Bachmeier. This time, she raised the child herself. By the late 1970s, Marianne was living in Lübeck, a historic port city in northern Germany, and working in the hospitality industry.

She ran or worked in a pub and was raising Anna as a single mother. Friends and acquaintances later described Anna as a lively, open, and trusting child.

Like many children her age, she attended primary school and spent time with neighborhood friends. For Marianne, Anna represented stability and hope after a turbulent early life.

The Crime That Shattered Everything

On May 5, 1980, Anna disappeared. According to court findings, the seven-year-old had left school early that day after an argument with her mother and was on her way to a friend’s house when she encountered Klaus Grabowski.

Klaus Grabowski was a local butcher with a prior criminal record for sexual offenses against minors. He had previously served time in prison.

During incarceration in the mid-1970s, he had undergone voluntary castration, a measure sometimes used at the time in Germany in cases involving repeat sexual offenders. Later, he received hormone treatment.

Grabowski abducted Anna and took her to his apartment. During the investigation and trial, he admitted to killing the child by strangulation.

He denied sexually abusing her, although prosecutors argued otherwise. He later claimed that the girl had attempted to blackmail him—an assertion the court rejected as not credible.

After killing Anna, Grabowski concealed her body near a canal. He was arrested later that same day after his fiancée contacted police with suspicions about his involvement. The discovery of Anna’s body devastated the community and intensified public outrage.

The Trial and Escalating Tensions

Grabowski’s trial began in early 1981 at the regional court in Lübeck. The proceedings were highly publicized. For Marianne Bachmeier, the trial was a painful experience.

She was forced to listen to the defendant’s statements, including claims that appeared to shift blame onto her daughter.

Observers later reported that the suggestion Anna had provoked or attempted to extort her killer deeply angered Marianne. She later said that hearing those allegations in court caused her extreme emotional distress.

Court security at the time was not as stringent as in later decades. On March 6, 1981—the third day of the trial—Marianne entered the courtroom carrying a small handgun, later identified as a Beretta pistol.

Accounts vary slightly in detail, but most reports agree that she fired eight shots at Grabowski, seven of which struck him. He died shortly thereafter from his injuries.

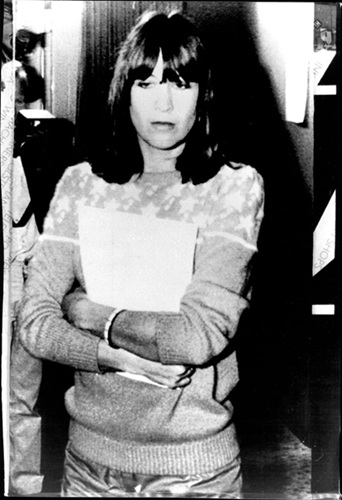

Immediately after the shooting, Marianne was restrained and arrested in the courtroom. According to witnesses, she made statements expressing that she had acted because he had killed her daughter.

The scene was chaotic. Judges, lawyers, and spectators were stunned. The killing of a defendant inside a courtroom was unprecedented in postwar German legal history.

Arrest and Charges

Marianne Bachmeier was taken into custody and charged with murder and illegal possession of a firearm. Her act was widely described as vigilantism—taking justice into one’s own hands rather than allowing the legal process to reach its conclusion.

During her own trial in 1982, Marianne stated that she had acted in an extreme emotional state. At times she described feeling as though she were in a dream-like condition when she fired the weapon.

However, expert witnesses suggested that bringing a loaded firearm into the courtroom and firing accurately required preparation and intent.

The court ultimately convicted her not of murder, but of premeditated manslaughter and unlawful possession of a firearm. In 1983, she was sentenced to six years in prison.

The court considered her emotional distress but also emphasized that the rule of law could not tolerate acts of personal revenge.

She served approximately three years before being released early on parole.

A Nation Divided

The case generated enormous media coverage in West Germany and internationally. Public reaction was sharply divided.

Some viewed Marianne as a grieving mother pushed beyond endurance. Others saw her actions as a dangerous precedent that undermined the legal system.

A survey conducted by the Allensbach Institute in the early 1980s reflected this division. Roughly a quarter of respondents believed her six-year sentence was appropriate.

Others felt it was too harsh, while another segment considered it too lenient.

The case sparked debates in newspapers, television programs, and academic circles about whether emotional trauma should mitigate criminal responsibility, and whether the justice system adequately addressed the suffering of victims’ families.

Media portrayals also shifted over time. Early reporting often emphasized Marianne’s grief and the brutality of her daughter’s murder.

Later coverage examined her complex personal history, including the fact that she had given two children up for adoption earlier in life and had experienced instability in her youth.

Public sympathy remained strong among many, but the broader picture became more nuanced.

Life After Prison

After her release from prison, Marianne sought a quieter life away from the intense scrutiny of German media. She emigrated to Nigeria for a period and married a German teacher who was working there. The marriage later ended in divorce.

In 1990, she relocated to Sicily, Italy, where she attempted to rebuild her life. Though she largely avoided public attention, her case remained part of Germany’s collective memory.

Newspapers and television programs occasionally revisited the story, especially when broader discussions about victims’ rights arose.

In 1994, thirteen years after the courtroom shooting, Marianne gave a rare interview on German radio. She spoke about the difference, in her view, between the act of killing a child and her own decision to kill the man who had murdered her daughter.

She suggested that she had acted in response to what she perceived as continued harm through the statements made during the trial.

In a 1995 interview with the German television channel Das Erste, she stated that her decision had been deliberate.

She said she had wanted to prevent further accusations and statements about her daughter from being voiced in court.

Illness and Death

In the mid-1990s, Marianne was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. As her health declined, she returned to Germany. She died on September 17, 1996, at a hospital in Lübeck at the age of 46.

She was buried next to her daughter Anna in Lübeck.

Legal and Ethical Legacy

The Bachmeier case remains a reference point in discussions about vigilante justice, victims’ rights, and the emotional toll of violent crime.

Legal scholars often cite it when analyzing how courts balance compassion with adherence to the rule of law.

Germany’s legal system, like many others, is built on the principle that justice must be administered by courts—not individuals.

The state maintains a monopoly on lawful punishment. Even in cases involving horrific crimes, private acts of retaliation are prohibited.

At the same time, the case intensified public conversations about how victims’ families are treated during trials. Many argued that courtroom procedures at the time did not sufficiently protect grieving relatives from distressing or provocative statements by defendants.

In subsequent decades, Germany introduced various reforms aimed at strengthening victims’ rights in criminal proceedings.

While not directly caused by the Bachmeier case alone, the national discussion it prompted contributed to broader awareness about the psychological impact of trials on families.

A Story That Still Resonates

More than four decades later, the story of Marianne Bachmeier continues to evoke strong emotions. For some, she represents a symbol of maternal grief taken to its most extreme form.

For others, she serves as a cautionary example of why even understandable anger cannot override the legal system.

Her actions cannot be separated from the context of her loss, nor can they be detached from the principles of law that govern democratic societies.

The tragedy of Anna’s murder remains at the heart of the story—a reminder of the devastating consequences of violent crime.

In Lübeck, the events of 1980 and 1981 are part of local history. Nationally, the case remains one of the most discussed examples of vigilante justice in modern Europe.

The death of a child is widely recognized as one of the most painful experiences a parent can endure. Marianne Bachmeier’s decision in that courtroom reflected profound grief and anger.

At the same time, her conviction reaffirmed the legal principle that justice must remain within the bounds of law.

Her life story—marked by hardship, tragedy, controversy, and illness—continues to prompt reflection about justice, accountability, and the human response to unimaginable loss.